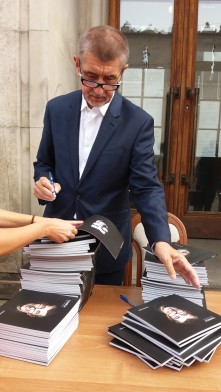

Babiš’s cap vs Zeman’s scarf

Czech prime minister Andrej Babiš‘s sporting a Trump-style baseball cap at the launch of his ANO movement’s Euro-election campaign, has attracted plenty of online derision.

Its ‘Strong Czechia’ (Silné Česko) slogan – intended to tell voters that billionaire populist and his MEPs will stick up for Czechia and its interests in the EU – is a kind of logical(ish) local equivalent of Make America Great Again.

Its ‘Strong Czechia’ (Silné Česko) slogan – intended to tell voters that billionaire populist and his MEPs will stick up for Czechia and its interests in the EU – is a kind of logical(ish) local equivalent of Make America Great Again.

It also conveniently plagiarises the eurosceptic opposition centre-right Civic Democrats’ 2017 policy paper promising a Strong Czechia in 21st Century Europe. (The movement’s main election slogan Protecting Czechia – Toughly and Uncompromisingly also echoes that used by Slovakia’s governing Smer in its failed 2016 election campaign.

Trump’s MGMA cap has been hailed as a political icon, signalling that despite the super-rich income bracket and background, he is culturally at one with regular folk. Some analysts have even suggested the way Trump wears it subtly connects with disenfranchised blue collar America.

But Babiš‘s cap – seemingly devised on the hoof by the Czech PM himself – doesn’t look a great piece of political marketing. Read More…

Expecting too much of Central Europe?

Brief commentary by me below written for Euractiv.sk on politics in the V4 and how Havel’s vision has been realised on partially – and sometimes in unexpected and unwelcome ways. Also accessible in Slovak and Polish.

Expecting too much of Central Europe?

By Dr Seán Hanley, senior lecturer at University College London´s School of Slavonic and East European Studies (SSEES). Havel’s warning about our most dangerous enemy not being dark forces of totalitarianism, but our own bad qualities deserve attention today – but from Europe-wide audience, writ…

Poland’s secrets and lies

Fair use for review purposes

Lustration, the systematic vetting and exclusion from high office of communist-era secret policemen, secret police informers and (sometimes) top-ranking Party bosses, has rather slipped out of the headlines in recent years.

The occasional high-profile case still surfaces. The Bulgarian authorities’ recent revelations that the psychoanalyst and philosopher Julia Kristeva collaborated with the country’s secret police in the early seventies to buy a few favours from the regime for family and friends, for example, briefly garnered considerable international media attention.

But these are the exceptions not the rule. The passage of time has blunted the relevance of lustration laws – anyone not now in their mid-late forties would have been children when communism fell.

And politically, a quarter of a century since the fall of communism, many Central and East European countries have either done what lustration they can or want to do, or bypassed the issue and let communist-era securocrats blend seamlessly into the new political and administrative elites. The recently “re-elected” Vladimir Putin epitomizes this second pattern.

Not so in Poland, argues Aleks Szczerbiak in his new book. Read More…

The world turned back upside down?

Fair use – review purposes.

Academically-authored death-of-democracy and liberalism-under-siege books are a rapidly expanding genre. The latest of these slim doomy volumes is Jan Zielonka’s Counter-Revolution: Liberal Europe in Retreat.

The book is an extended essay written in the form of a letter to the late Ralf Dahrendorf, whose Reflections on the Revolution in Europe (1990) offered a similar, but more optimistic take on Europe’s prospects in the immediate aftermath of 1989. Tellingly, while Dahrendorf addresses an anonymous ‘gentleman in Warsaw’, this imaginary exchange takes place between two British-based European scholars.

From the outset, Zielonka makes clear he’s not setting out to write yet another tract about populism. Instead, he offers us a reflection on the weaknesses and limitations of liberalism in Europe – ‘a self-critical book by lifelong liberal.’

Whether in economics, democracy, European integration or when meeting the challenges of migration and climate change, liberals have, Zielonka argues, mucked things up since the fall of communism. Liberalism has mainly served elites, economic winners and vested interests becoming ‘a comprehensive ideology of power: set of values, way of government and cultural ethos’. Read More…

How Zeman won – a tale of two populisms?

Photo: Kremlin.ru, CC BY 4.0, Link

The opinion polls were right about one thing. The second-round run-off for Czech presidency on 26-27 January were a close contest.

But, contrary to what most polls had forecast, it was sitting president Miloš Zeman who claim a narrow victory, beating his independent opponent Jiří Drahoš, the former head of the Czech Academy of Sciences, by 51.4% – 48.6%.

In their own way, both candidates were signs of the populist times – and proof that populism need not just take the form of outsider parties emerging from the fringes (although, in billionaire prime minister designate Andrej Babiš and his ANO movement, or radical-right Freedom and Direct Democracy (SPD) grouping of Tomio Okamura, the Czech Republic has these too).

Of the two presidential contenders in the run-off, Zeman was the more textbook populist. Since coming out political retirement in 2009, the former Social Democrat prime minister – who claims to speak for the “bottom 10 million” in a country with a population of 10.56 million – has combined a penchant for left-wing economics with outspokenly nationalistic and illiberal stances on migration and European affairs. Read More…

Zeman again?

Photo: David Sedlecký via Wikimedia– CC BY-SA 4.0

Once sedate and dull, Czech politics has recently been serving up non-stop political drama. First, October’s parliamentary elections dealt a shattering, but not fatal, blow to established parties.

Then the election winner, the billionaire-politician and fraud indictee, Andrej Babiš struggled to form a government with any of the other eight parties in parliament opted instead in December to form a minority administration with uncertain prospects (it faces a vote of confidence tomorrow). Now creeping up on us after a low-key campaign come the Czech presidential elections, whose first round takes place on 12-13 January.

The relatively low profile of the election is partly down to the incumbent. Having announced in March that he would run for a second term, president Miloš Zeman has opted for a Czech version of the Rose Garden Strategy by officially not campaigning, refusing to give pre-election interviews or appear in debates with other candidates; and according to his transparent online campaign account spending pretty much zilch.

The reality is that for many months presidential visits to regions and provincial towns, fielding undemanding questions from generally sympathetic crowds, have served as a surrogate, under-the-radar campaign.

Zeman’s non-campaign

Fair use: relevant illustration, low res

Zeman’s non-campaign now also features expensive-looking billboard and newspaper advertising to elect Zeman Again (Zeman znovu) paid for by the Friends of Miloš Zeman – a previously dormant civic association founded in 2008 to relaunch Zeman from political retirement.

To some extent, these tactics seems to reflect Zeman’s state of health. Although rumours of cancer and other life-threatening conditions has been vigorously rebutted, the president suffers diabetes and a nerve condition – possibly arising as a complication – affecting his legs which visibly limits his mobility. The president’s alcohol and tobacco consumption have also long been a source of concern to his doctors.

In other ways, however, Zeman’s semi-visible campaign is a shrewd political move. For supporters Zeman is a flawed, but decent politician, who stands up for the interests of ordinary people outside the better-off world of Prague and big cities and also sticks up for Czech national interests. For his many detractors Zeman is a boorish authoritarian illiberal nationalist and a national embarrassment, tarnishing the Czech Republic’s good name.

As well as lapses of decorum such as appearing drunk at ceremonial occasion and using the c-word in a radio broadcast, Zeman has shared a platform with fringe anti-Islamic extremists and come out as the only EU head of state to publicly endorse Donald Trump before the US elections in 2016.

More worrying still has been his cavalier attitude to the Czech constitution. His appointment in 2013 of a presidential caretaker government of supposed technocrats over the heads of political parties flouted previous constitutional practice. He has at various times, suggested that, creatively interpreted, the constitution could him allow him to dismiss the government; leave ministers in office following a prime minister’s resignation; or leave his ally prime minister Andrej Babiš in office, rather than dissolve parliament if all three constitutionally allowed attempts at forming a government were exhausted.

Polls suggest, however, Zeman, who has been picking up support since the launch of the December billboard, has a solid base of support predominantly among poorer, older, more left-wing, less well-educated Czechs. He is likely to top the first-round poll by a clear margin with 43-44% of the vote, but may face a stiffer contest in the second, run-off round on 26-27 January.

The challengers

As in the first direct presidential elections in 2013, Zeman faces eight challengers. However, this year political parties have taken a back seat. Many have realised that they simply lack a broad enough appeal or any credible enough candidates to have a serious run at the presidency.

The one party that could have done so, Andrej Babiš’s ANO movement – said at one time to have considered running the popular defence minister (now foreign minister) Martin Stropnický for presidency – chose not to do so: for Babiš keeping to his informal pact with Zeman and getting into government were by the important priorities. If, as expected, his new minority administration loses its upcoming parliamentary vote of confidence, Zeman will play a key role by re-nominating Babiš as prime minister for a second, and probably decisive, effort a forming a government.

All of but two of Zeman’s challengers are thus non-party independents running on vague centrist or centre-right platforms – the two exceptions being the candidate of the tiny, populist Common Sense party Petr Hannig and Jiří Hynek of the Realists, a well-funded but peripheral conservative grouping. Former prime minister Mirek Topolánek, who headed a Civic Democrat-led (ODS) governments of 2006-9, running as independent, also seems to be attracting some backing from parts of his former party, helped by outspoken attacks on Zeman questioning the president’s health.

Polls suggest, however, that Zeman has only two serious challengers: Jiri Drahoš, the former head of the Czech Academy of Sciences, and the journalist, lyricist and music producer turned betting tycoon and philanthropist, Michal Horáček. Although Horáček has waged a slicker campaign, most polls show him in third place with Drahoš the clear favourite to make it into the run-off against Zeman on 26-27 January.

President Drahoš?

Photo: Tomas Masin – via Wikimedia CC BY-SA 4.0

Although keeping a (for him) low profile, Miloš Zeman has had a good campaign. He has been picking up support following the launch of December’s billboard campaign with bookmakers’ odds making him the clear favourite and little sign of his rivals generating much momentum or public excitement.

However, polls still suggest that Zeman will lose by a clear margin in a run-off against Drahoš, who is forecast to gain most of the first round votes cast for other candidates – emulating a strategy seen in presidential elections in Slovakia and Romania in 2014, when previously little-known independents overhauled seemingly dominant left-wing populists in the second round.

Throughout Drahoš has cultivated a centrist and non-confrontational image, telling interviewers that he had a vision, but no political programme. He also made clear that – while he wouldn’t have appointed Andrej Babiš prime minister without fraud charges hanging over him breing resolved – he saw as a mainstream politician with a clear electoral mandate whose government deserved the backing of other mainstream parties.

Zeman will, therefore, be hoping that his non-campaign has been well pitched enough to rally his core support among poorer, older, less well-educated Czechs, while leaving diverse groups of voters opposed to him unmobilised. His most likely path to victory would be to get enough votes behind him to narrowly win the election outright in the first round. The fact that his key challengers are offering only dignified public personas and good CVs, rather than any compelling positive vision of a liberal and outward looking Czechia may turn out to be Zeman’s greatest asset.

Czechia: a minority administration with big ambitions

Photo: Jan Polák CC BY-SA 4.0 Wikimedia Commons

On 13 December, Czech President Miloš Zeman formally appointed a minority government led by the billionaire-politician Andrej Babiš, whose ANO movement emerged as the clear winner of parliamentary elections on 20-21 October, gaining 78 seats in the 200-member Chamber of Deputies.

The October elections saw no fewer than nine parties (including ANO) gain representation in the Czech parliament, producing a highly fragmented political landscape with no credible alternative to an ANO-led government: the second largest party, the centre-right Civic Democrats (ODS) held only 25 seats

Given ANO’s broadly centrist position, a range of ideologically coherent coalitions should, in principle, have been possible.

Babiš himself indicated that he preferred a two-party coalition with the Civic Democrats, but would be willing to enter government with his partners from the outgoing coalition, the Social Democrats (ČSSD) and Christian Democrats (KDU-ČSL), the small independents grouping STAN or the left-liberal Pirate Party (ČPS), who entered parliament for the first time in October. He ruled out the Communists, the radical right Freedom and Direct Democracy (SPD) grouping and the liberal, pro-European TOP09, whose (then) leader Miroslav Kalousek was a persistent and forthright critic.

However, it quickly became apparent, that none of these potential partners were willing to enter a led a Babiš-led government. Read More…

Czech elections: Is Babiš heading for a Pyrrhic victory?

Photo (cropped): Jiří Sedláček CC BY-SA 4.0

There is only one major issue in the Czech Republic’s upcoming elections on 20-21 October – and his name is Andrej Babiš.

Since bursting onto the political scene – and straight into government – at the 2013 elections, the Slovak-born agri-food billionaire and his ambitions have defined Czech politics in the last five years. Having spent four years as junior partner in acrimonious coalition government with the Czech Social Democrats (ČSSD) and the smaller Christian Democrats (KDU-ČSL) and consistently topped every poll since early 2014 – Babiš and ANO his movement now seem set to win next weekend’s election by a considerable margin.

Polls suggest ANO will receive just under 30% of the vote, despite Babiš and several associates from his Agrofert conglomerate being implicated in and then formally charged with embezzling some two million euro in EU subsides intended for SMEs in 2008 for Babiš’s showpiece ‘Stork’s Nest’ eco-farm, by concealing its real ownership. As in 2013 Babiš and ANO are pitching themselves as non-ideological citizens’ movement doing battle with corrupt and ineffective ‘traditional parties’ – who Mr Babiš says have hamstrung him in government, victimised him with bogus anti-corruption probes and accusations of wrongdoing which led to his ousting as finance minister in May.

ANO thus seems set to become the dominant force in an otherwise fragmented political landscape: none of the seven other parties projected to enter the Chamber of Deputies is likely to exceed 15 per cent support. Read More…

How I jez didn’t make it and lost the general election

Photo Rwendland CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

I am a huge fan of the election simulation game Prime Minister Infinity and, true to form, publishers 270soft have come out with an update just in time for the snap UK 2017 general election.

Having struggled in the role of Ed Miliband playing 2015 version – though doing better than the real Ed in getting a hung parliament – I again stepped into the shoes of an embattled an Labour leader, this time Jeremy Corbyn.

I tried to play like the real Jez running a generally positive campaign focusing on policies for health and education with an occasional jab at the Tories for being champions of austerity and enemies of public services.

As in real life, however, things didn’t go to plan. A couple of weeks in, the polls had Labour stuck under 30% with predictions of Tory landslide of 400 seats – and the worthy policy speeches of Corbyn-me simply not cutting through in terms of media coverage.

Having started off optimistically venturing into a few Conservative marginals, I quickly found myself like the real world Corbyn retreating to heartlands the north of England and Wales, visiting places like Hartlepool, Hyndburn and Middlesbrough, trying to stop the possible loss of supposedly safe seats to the Tories. Read More…

Where the EU went wrong in Eastern Europe

Photo: KrysztofTe Foto Blog (cropped) CC BY 2.0

One election, it seems, really can change everything.

Once feted for having bucked both the populist trend and the global recession, in early 2017 Poland was facing international condemnation. Moves by the Law and Justice government have come straight out of the playbook shared by the likes of Hungarian strongman Viktor Orbán. It’s moved quickly to neuter the constitutional court; to take control of the state media; to defund unfriendly NGOs or regulate them into irrelevance; to put its own people in charge of public institutions; and has given every sign of being prepared to ride out waves of protests and ignore international criticism.

Recent footage of opposition deputies occupying the podium of the Sejm and chaotic and hastily convened parliamentary voting by government deputies in back rooms was more reminiscent of the crisis-hit democracies of southern and southeastern Europe than the democratic trailblazer once hailed by European Union heavyweights.

To be clear, Poland is not yet Hungary, the EU’s other major backsliding headache. Law and Justice has only a small parliamentary majority, not the supermajority needed for a Hungarian-style constitutional rewrite. Protesters have been more assertive and quicker to take to the streets.

Nor does Poland have a powerful far-right party like Hungary’s Jobbik waiting in the wings to claim the role of “real” opposition if the ruling party falters. Poland’s opposition may yet manage to use social movements as a rough-and-ready substitute for weakened constitutional checks and balances — and may perhaps eventually make a winning return at the polls. But even in this (far-from-certain) best-case scenario, the country’s institutions are likely to emerge from this period badly damaged.

But the speed at which Poland’s and Hungary’s apparently successful democracies have unravelled points toward a problem that has tended to be overlooked amid the latest political developments: Contrary to appearances, liberal democracy was never solidly rooted in Eastern Europe. Read More…

You must be logged in to post a comment.